Integrin Interactome & the Complexity of Fascial Dynamics:

What Does This Mean for Acupuncturists & Myofascial Therapists?

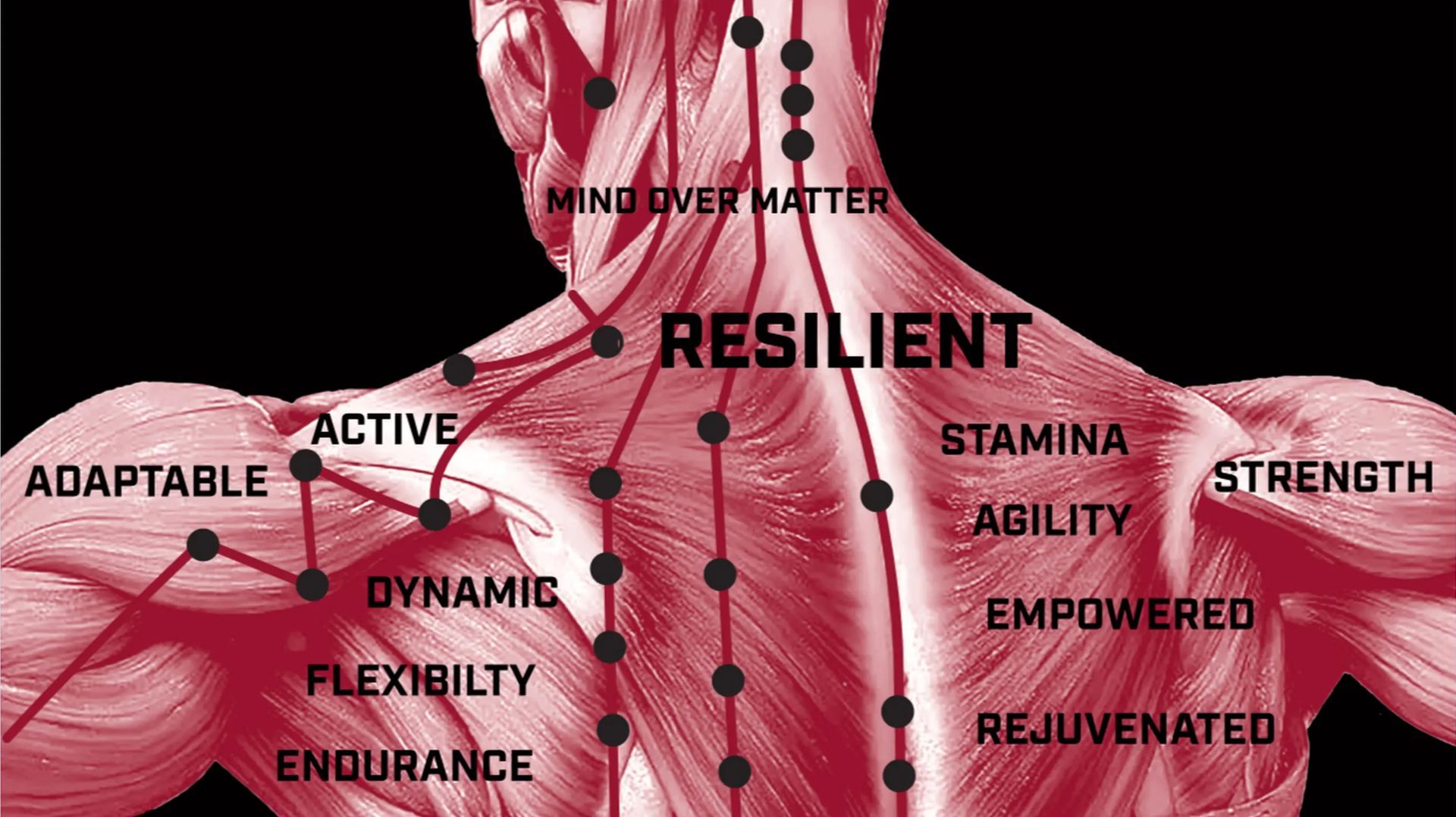

Integrins as Mechanoreceptors

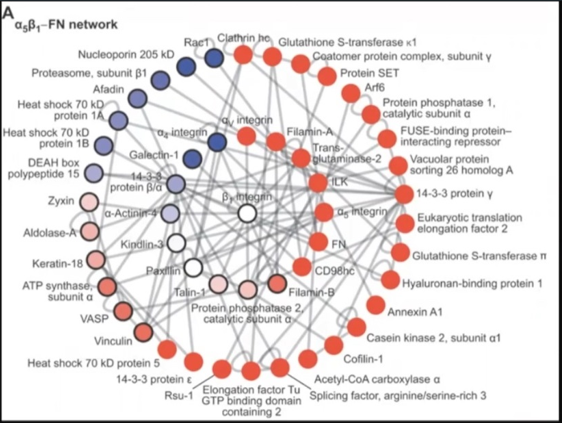

Integrins, described as the "first mechanoreceptors" (Khan et al., 2021), are essential transmembrane proteins that bridge extracellular matrix (ECM) signals and intracellular cytoskeletal dynamics. This intricate image shows the vast network of 250 proteins associated with integrin adhesions, highlighting how these interactions span from structural to functional cellular responses. These signals influence cell behavior, such as adhesion, migration, and remodeling, which are foundational processes in musculoskeletal function.

Fascial systems, as explored by Schleip et al. (2012), form part of the ECM and play a vital role in how forces are transmitted through the body. The understanding of integrins as mediators of these forces underscores how interconnected the fascia, cellular processes, and mechanical stimuli are.

The Limits of Simplistic Models

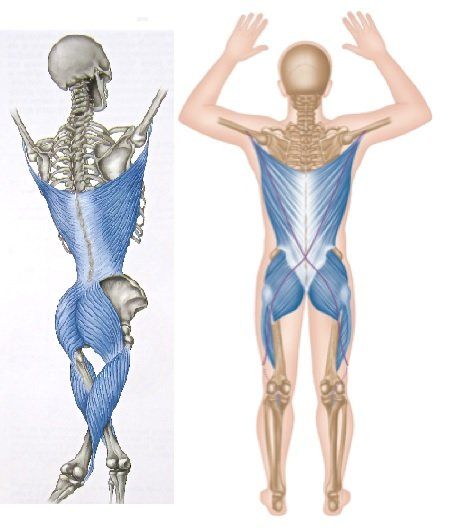

Janda’s fascial sling theory emphasizes relationships between inhibited (weak) and shortened (overactive) muscle groups, often attributing dysfunction to predictable compensatory patterns (Page et al., 2010). However, as the integrin interactome (Khan et al., 2021) demonstrates, the process is far more complex. Muscle behavior is not solely dictated by local dynamics but by systemic and cellular interactions influenced by the ECM, mechanical load, and signaling pathways.

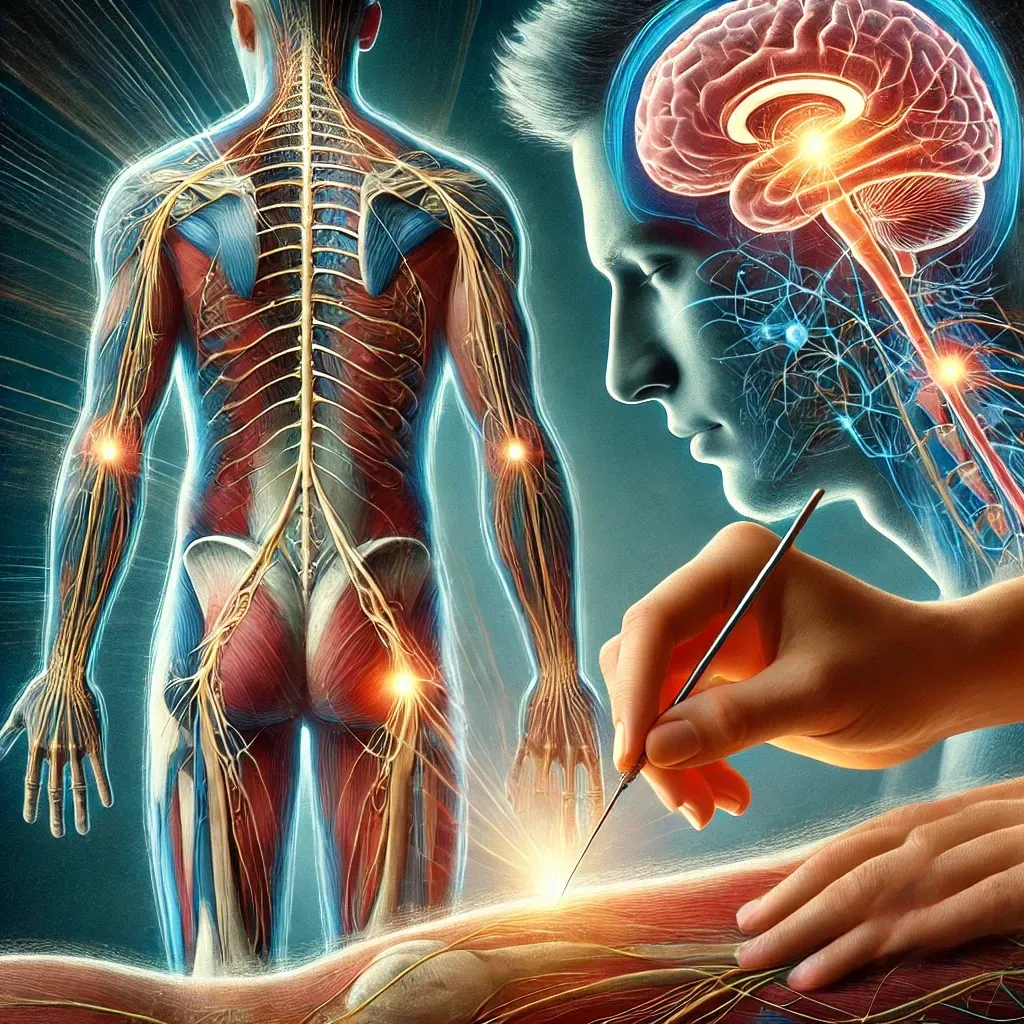

While fascial therapies like myofascial release or acupuncture target localized issues, research indicates that these gains may be short-lived unless combined with neuromuscular training (Schleip et al., 2012). The absence of proper re-education of motor patterns can result in recurring dysfunction.

Deep ↔ Superficial Continuum

The image’s focus on the "deep to superficial" principle (Khan et al., 2021) is a stark reminder that fascial slings are not isolated to muscle tissue but are intimately tied to deeper cellular processes mediated by integrins. For example, integrins modulate responses to physical stimuli, forming feedback loops between tissue deformation (external loads) and cellular responses (internal tensioning).

Vleeming & Stoeckart (2007) elaborated on the functional role of the thoracolumbar fascia, a key component in the posterior myofascial sling. They demonstrated how load transfer between deep and superficial layers relies on the integration of cellular and fascial networks. This disrupts the simplicity of the "inhibited vs. shortened" model, as one cannot view muscular dysfunction in isolation from the underlying connective tissue, cellular processes, and neural signaling.

Systemic Complexity Beyond Mechanical Dichotomies

The proteins interacting with integrins, such as talin, vinculin, and actin, illustrate how cellular adhesion and cytoskeletal remodeling underlie all tissue dynamics (Khan et al., 2021). Janda’s model, while effective clinically, does not account for how mechanotransduction at the cellular level alters the ECM and, consequently, the fascial and muscular relationships.

Research supports that therapies addressing fascia—like acupuncture or myofascial release—often yield temporary mobility improvements due to their localized effect. However, these gains are not sustainable without neuromuscular re-education (Vickers & Linde, 2014). Functional movement requires reinforcing the new range of motion with proper motor control to avoid a return to dysfunctional patterns.

Revisiting Fascial Slings with New Understanding

- Janda’s theory (Janda, 1983; Page et al., 2010) works well as a clinical heuristic but is challenged by this deeper understanding of integrin-mediated processes. Fascial and muscular behaviors arise not from simple “shortened vs. inhibited” paradigms but from dynamic, multidirectional influences that encompass cellular mechanics, systemic adaptations, and environmental inputs.

- Myers (2009) and Schleip et al. (2012) collectively underscore the importance of viewing fascial slings as holistic systems. By considering this complexity, practitioners can appreciate that interventions must address the fascial and cellular ecosystem as a whole, moving beyond isolated muscle treatment.

To ensure sustainability, manual therapies like myofascial release or acupuncture should always be paired with neuromuscular training. This integrated approach teaches the nervous system to stabilize the newly gained range of motion, ensuring functional mobility. As Myers (2009) explains, the fascial system thrives on movement efficiency, which can only be achieved with active engagement through neuromuscular exercises.

Conclusion

The integrin interactome (Khan et al., 2021) demonstrates that the dynamics of musculoskeletal systems extend far beyond classical concepts like Janda’s fascial slings. These interactions encompass cellular and extracellular mechanics influenced by integrin-mediated mechanotransduction, adding layers of complexity to the functional relationships between muscles, fascia, and movement patterns.

Practitioners who integrate insights from the integrin interactome (Khan et al., 2021) with foundational theories of fascial slings (Janda, 1983; Myers, 2009; Schleip et al., 2012) will find themselves equipped to approach movement dysfunction with greater precision and adaptability. Understanding these relationships allows for a more nuanced, comprehensive approach to human movement and rehabilitation strategies.

FAQ: What Does This Mean for Acupuncturists and Myofascial Therapists?

1. What does this mean for acupuncturists and myofascial therapists?

For acupuncturists and myofascial therapists, the integrin interactome highlights the systemic complexity of musculoskeletal and fascial dynamics. These findings emphasize that therapies aimed at releasing tension or adhesions in fascia must go beyond superficial techniques. Sustained results depend on addressing the deeper neuromuscular and biochemical factors influencing the fascia.

2. Why are mobility gains from acupuncture and myofascial release often not sustainable?

While therapies like acupuncture and myofascial release temporarily improve mobility, research shows these gains are not sustainable unless paired with neuromuscular training (Schleip et al., 2012; Vickers & Linde, 2014). Without retraining motor patterns, the nervous system often reverts to dysfunctional compensations.

3. How does neuromuscular training support mobility improvements?

Neuromuscular training creates sustainable mobility by teaching the nervous system to stabilize and use the new range of motion effectively. According to Janda (1983), functional movement depends on the coordination of inhibited and shortened muscles. Corrective exercises reinforce this balance, ensuring long-term results.

4. What should an integrated approach include for lasting results?

For lasting mobility gains, practitioners should combine:

- Fascial release techniques like acupuncture or myofascial release.

- Neuromuscular training, including proprioceptive and dynamic stability exercises.

- Functional strength training to reinforce proper movement patterns.

5. How can acupuncturists and therapists incorporate neuromuscular training?

Acupuncturists and therapists can collaborate with movement professionals or integrate basic motor control exercises into their sessions.

For example:

- Including proprioceptive exercises post-treatment.

- Educating patients about movement efficiency and posture.

- Referring patients for progressive strength training programs.

References

- Janda, V. (1983). Muscle Function Testing in Functional Pathology. Prague: Charles University.

- Page, P., Frank, C., & Lardner, R. (2010). Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance: The Janda Approach. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Myers, T. W. (2009). Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Schleip, R., Findley, T. W., Chaitow, L., & Huijing, P. A. (2012). Fascia: The Tensional Network of the Human Body: The Science and Clinical Applications in Manual and Movement Therapy. London: Churchill Livingstone.

- Vickers, A., & Linde, K. (2014). "Acupuncture for Chronic Pain." JAMA, 311(9), 955-957.

- Vleeming, A., & Stoeckart, R. (2007). "The Role of the Posterior Layer of the Thoracolumbar Fascia in Load Transfer through the Pelvic Girdle and Its Relationship to Myofascial Slings." Clinical Biomechanics, 22(1), 89-94.

- Khan, K. M., et al. (2021). Integrin Adhesion Network Interactions.