The Resilient Mindset:

How Belief Shapes Recovery

Introduction

Resilience is more than just physical toughness—it is a mindset that determines whether one remains trapped in chronic pain or achieves recovery. Scientific research shows that our beliefs, expectations, and pain perception play a fundamental role in healing (Lumley et al., 2011). The ability to reframe pain, remain active, and foster positive expectations can alter the way the nervous system processes pain, leading to real physiological improvements (Trachsel et al., 2023).

Yet, many people are told by doctors: “There’s nothing more we can do.” This statement, while often unintentional, can worsen pain by reinforcing a nocebo effect—a phenomenon where negative expectations increase pain and disability (Colloca, 2017).

This article explores the scientific evidence behind pain perception, nocebo effects, movement-based recovery, and cognitive biases like the Dunning-Kruger effect. We will also examine case studies of people who defied grim medical prognoses, demonstrating that resilience is a powerful factor in pain recovery.

Pain Perception: How Expectations Influence Pain

Pain is not just a sensory experience—it is shaped by our expectations, beliefs, and emotions (Trachsel et al., 2023). Research has consistently shown that the way we think about pain can either amplify or reduce it (Lumley et al., 2011).

The Placebo Effect in Pain Perception

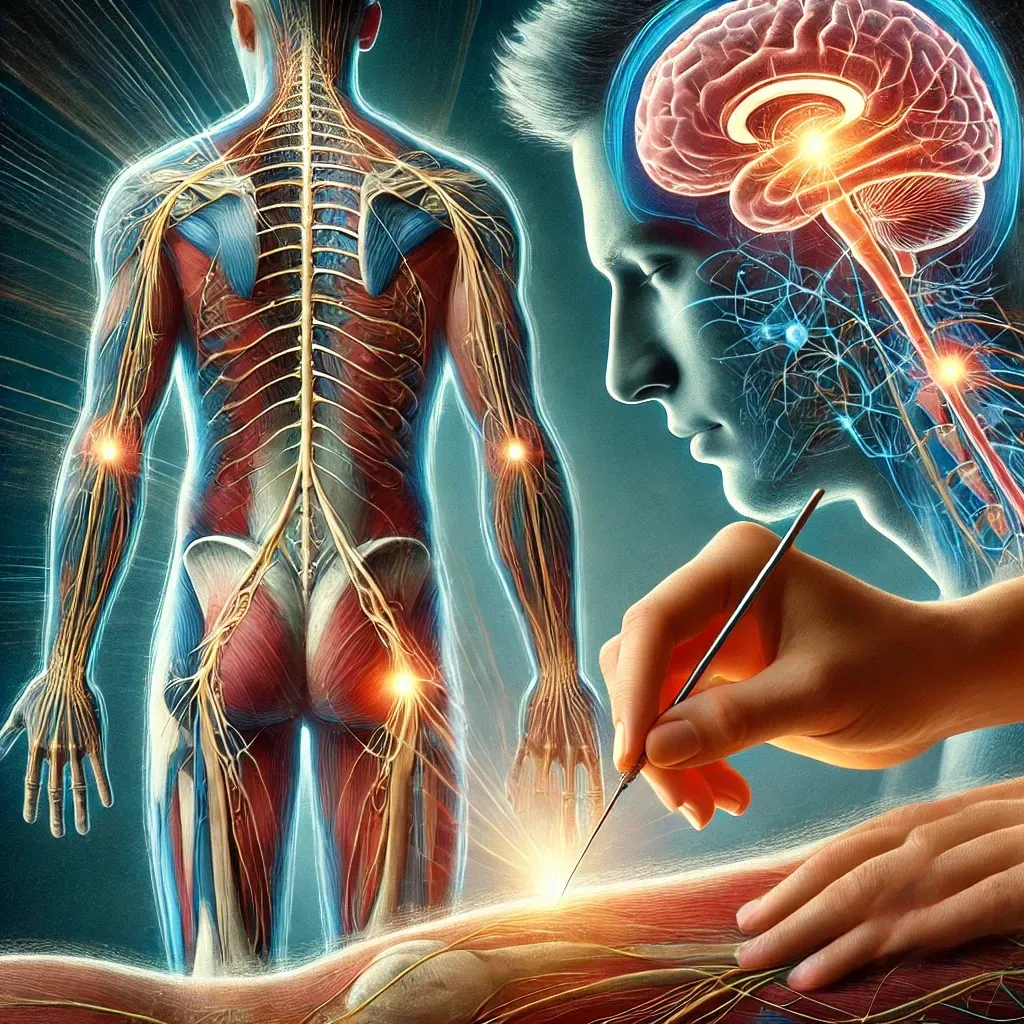

The placebo effect is one of the most well-documented examples of how expectations shape pain. Placebo studies reveal that believing a treatment is effective can activate the brain’s own pain-relieving mechanisms, including the release of endorphins and dopamine (Benedetti, 2020). Neuroimaging studies confirm that placebos reduce activity in pain-processing areas of the brain, proving that expectations can directly modify pain perception (Zunhammer et al., 2021).

Conversely, when patients expect pain to worsen, it often does. This phenomenon is known as the nocebo effect.

The Nocebo Effect: When Negative Expectations Increase Pain

Just as positive expectations can reduce pain, negative expectations can intensify it. The nocebo effect occurs when patients develop heightened pain, disability, or side effects due to negative beliefs about their condition or treatment (Colloca, 2017).

Clinical Evidence of the Nocebo Effect

- Verbal Suggestions and Pain Sensation: In an experimental study, simply telling patients that an upcoming procedure would be painful caused significantly higher pain ratings, even when the actual stimulus was mild (Colloca, 2017).

- Statins and Muscle Pain: In 2013, widespread media coverage suggested that cholesterol-lowering statins caused muscle pain. Following these reports, thousands of patients reported muscle pain and discontinued their medication. However, controlled studies later revealed that many of these symptoms were psychogenic—patients who expected muscle pain were more likely to experience it, even when given an inactive placebo (Brazil, 2018).

These findings highlight how healthcare language matters. Telling a patient, “Your spine is severely degenerated,” can instill fear, increasing their pain levels and reducing their likelihood of recovery (Geneen et al., 2017).

Case Studies: Defying the Odds in Pain Recovery

Despite being told that recovery is impossible, many patients reclaim mobility and become pain-free through movement, mindset shifts, and alternative approaches.

1. Chronic Back Pain and Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT)

A randomized controlled trial examined the effects of Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT), a psychological intervention designed to shift patients’ beliefs about chronic back pain. Participants who underwent PRT experienced significant pain relief, with 66% becoming nearly or fully pain-free, compared to only 20% in the control group (Ashar et al., 2021). This trial demonstrated that altering pain beliefs and fear avoidance can lead to substantial recovery.

2. Placebo Surgery for Knee Osteoarthritis

In a landmark study, patients with severe knee osteoarthritis were randomly assigned to real arthroscopic surgery or a sham (placebo) surgery. Surprisingly, both groups experienced identical pain relief (Moseley et al., 2002). This finding suggests that belief in treatment may be as powerful as the surgery itself.

3. Overcoming Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

CRPS is often considered incurable, but case studies document patients fully recovering through graded motor imagery and mirror therapy. In one case, a patient with CRPS regained full limb function after months of structured mental visualization exercises (Moseley & Flor, 2012).

These cases reinforce a crucial message: even when medical diagnoses seem hopeless, recovery is possible when the mind and body are retrained.

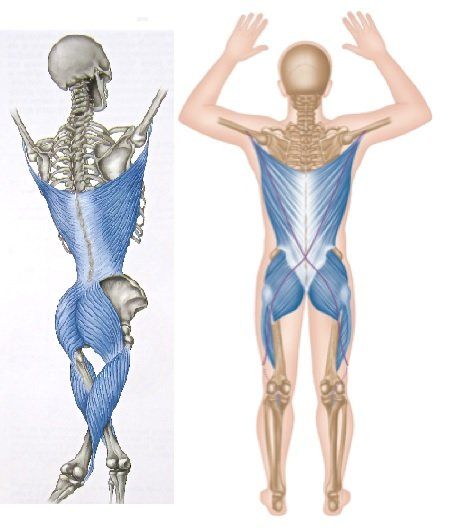

Movement as Medicine: Why Motion is Key to Recovery

When people experience pain, the natural instinct is to avoid movement. While rest is beneficial in the early stages of injury, prolonged avoidance of movement can worsen pain and disability (Geneen et al., 2017).

Breaking the Fear-Avoidance Cycle

- The Fear-Avoidance Model: Chronic pain often persists because patients develop fear of movement, leading to muscle weakness, stiffness, and increased pain. This vicious cycle is known as the fear-avoidance model (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000).

- Graded Exposure Therapy: Research has shown that gradual reintroduction of movement reduces pain and improves function in chronic pain patients (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000).

- Exercise for Chronic Pain: A Cochrane review found that exercise is one of the most effective non-drug interventions for chronic pain, providing long-term pain relief comparable to medications (Geneen et al., 2017).

In short, movement is medicine. Safe, progressive exercise helps rewire pain pathways, improve mobility, and rebuild confidence.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Overconfidence in Pain Understanding

The Dunning-Kruger effect describes how people with low knowledge often overestimate their expertise (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). This bias appears in pain management in two ways:

- Healthcare Providers: Some doctors dismiss alternative approaches (e.g., acupuncture, graded exposure) without understanding pain neuroscience. Overconfidence in outdated pain models can prevent patients from receiving the best care (Geneen et al., 2017).

- Patients: Many chronic pain sufferers believe bed rest is the only solution or that pain always equals tissue damage, when in reality, movement and mindset shifts can rewire pain pathways (Zunhammer et al., 2021).

By staying open-minded and continually learning, both patients and providers can avoid false confidence and embrace evidence-based solutions for pain recovery.

Conclusion: Resilience is the Key to Recovery

Pain is not just a sensory experience—it is deeply influenced by expectations, movement, and mindset. The resilient mindset acknowledges that:

- Pain does not always mean damage.

- Movement is essential for recovery.

- Negative beliefs can worsen pain, while positive beliefs can promote healing.

Ultimately, resilience is the missing ingredient in pain recovery. Those who believe in their ability to heal, embrace movement, and challenge negative expectations are often the ones who defy the odds and reclaim their mobility.

References

- Ashar, Y. K., Gordon, A., Schubiner, H., Uipi, C., Knight, K., Anderson, Z., ... & Wager, T. D. (2021). Pain reprocessing therapy for chronic back pain: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(11), 1189-1197.

- Benedetti, F. (2020). Placebo effects: From the neurobiological paradigm to translational implications. Neuron, 106(1), 116-132.

- Brazil, R. (2018). Nocebo: The placebo effect’s evil twin. The Pharmaceutical Journal.

- Colloca, L. (2017). Nocebo effects can make you feel pain. Science, 358(6359), 44.

- Geneen, L. J., et al. (2017). Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD011279.

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134.

- Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Linton, S. J. (2000). Fear-avoidance in chronic pain. Pain, 85(3), 317-332.